[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]In a post from Merriam-Webster’s Words at Play, Mary Norris (Between You & Me) called Meet Mr. Hyphen the “best thing ever written about hyphens.”

First: All hail the Comma Queen!

Second: If Norris’s assessment intrigues you, then you’re probably a copy editor.

I read that post years ago, and because the book was out of print, I had to go to some trouble to track it down—which I did happily. But then life got busy and it sat on my bookshelf for far too long.

I always liked that Mr. Hyphen was there, though. You might know the feeling of having a book, especially a book with a tinge of mystery because of its relative unavailability, that you purposefully put off reading to retain the magic.

Eventually, however, I could savor the want of it no more, and I traded mystery for experience.

The Context

Edward N. Teall, a proofreader on the 1934 Webster’s New International Dictionary, Second Edition, wrote Meet Mr. Hyphen in 1937 after years of studying compounding. So when he refers to the ’90s, he’s referring to the 1890s.

In other words, you won’t find any references to two of my favorite bands, Faith No More and Soundgarden (and even my ’90s are feeling more and more distant).

This was before macros. Before crtl+F. Before PerfectIt.

Hats off to editors past.

Teall may have written nearly a century ago, but his concerns will strike you as modern. Teall talks about the challenges of compounding (open, closed, or hyphenated) because of the rapid addition of new words related to automobiles, airplanes, movies, and radio. He notes language’s “superabundance of material.”

Sound familiar?

You imagine his joy and wonder if he were to see the pace of language change today.

“We are putting words together in a way that multiplies their power and widens their scope,” he wrote.

And we still are.

No Easy Answers

Teall exhibits a childlike enthusiasm for the art of compounding (“an art, because personal preferences and individual judgments will always be decisive”).

Speaking of childlike—the word, that is—Teall has a wonderful aside about the practice academics had apparently proposed of hyphenating -like words based on whether they were literal or metaphorical (when combined with child or death, for example).

Teal dismisses the practice as impractical, but it gets at the kind of thinking Teall employs, a kind of double-clicking* on the logic of the compound itself instead of a strictly grammatical, role-based determination that can be applied broadly and mechanically. Though wouldn’t that be easier, we weep.

* I hadn’t heard double-clicking used this way until a recent episode of the fabulous That Word Chat, featuring Anne Curzan. Apparently it’s business jargon, but I kind of like it.

As Teall says, “The English language simply is not logical,” so easy answers are likely in short supply. (Have you checked the page count on the Chicago Manual’s hyphenation table?)

Teall: “The compounding of words is not sport for specialists, not a freakish, fantastic field of theory; not academic, not aristocratic. It is part of the plain business of conveying ideas through writing or print. It has value in private and professional correspondence; it affects the worth, in accuracy and in validity, of legislative enactments and state documents. It is important to all who write or print.”

He goes on: “Clean compounding is a source of strength. Slack, untidy compounding is in itself a weakness.”

And later the most important point: “[Good compounding] prevents ambiguity and misunderstanding.”

Teall’s Method

It’s unlikely many have thought more about compounding and hyphens than Teall. What may strike the reader is the love he brings to this peculiar passion. He seems dedicated to a task he knows will forever elude ironclad laws or rules one can apply without thought and across circumstance.

And he revels in the chase.

“Cultivate his acquaintance—but keep him in his proper place. Don’t let him crowd in where he doesn’t belong, but insist on his doing what is expected of him. He’s a good fellow, but he has to be watched.”

There’s also a kindness in his approach, and his practice is one we might do well to apply to all areas of editing:

“First, analysis. The formulation of principles. Next, the casting of rules. Finally, determination not to let any rule override consideration of clarity and exactness of statement in any situation that may arise in the course of composition.”

For us, words of assurance:

“This is salvation for the stylesheet makers—for writers, editors, secretaries—for all who put words on paper. First, the making of a workable system; then, clear perception and effective acceptance of the fact that any rule may be laid aside in emergency—and criticism on the ground of inconsistency may be heavily discounted.”

Stick Around, Mr. Hyphen

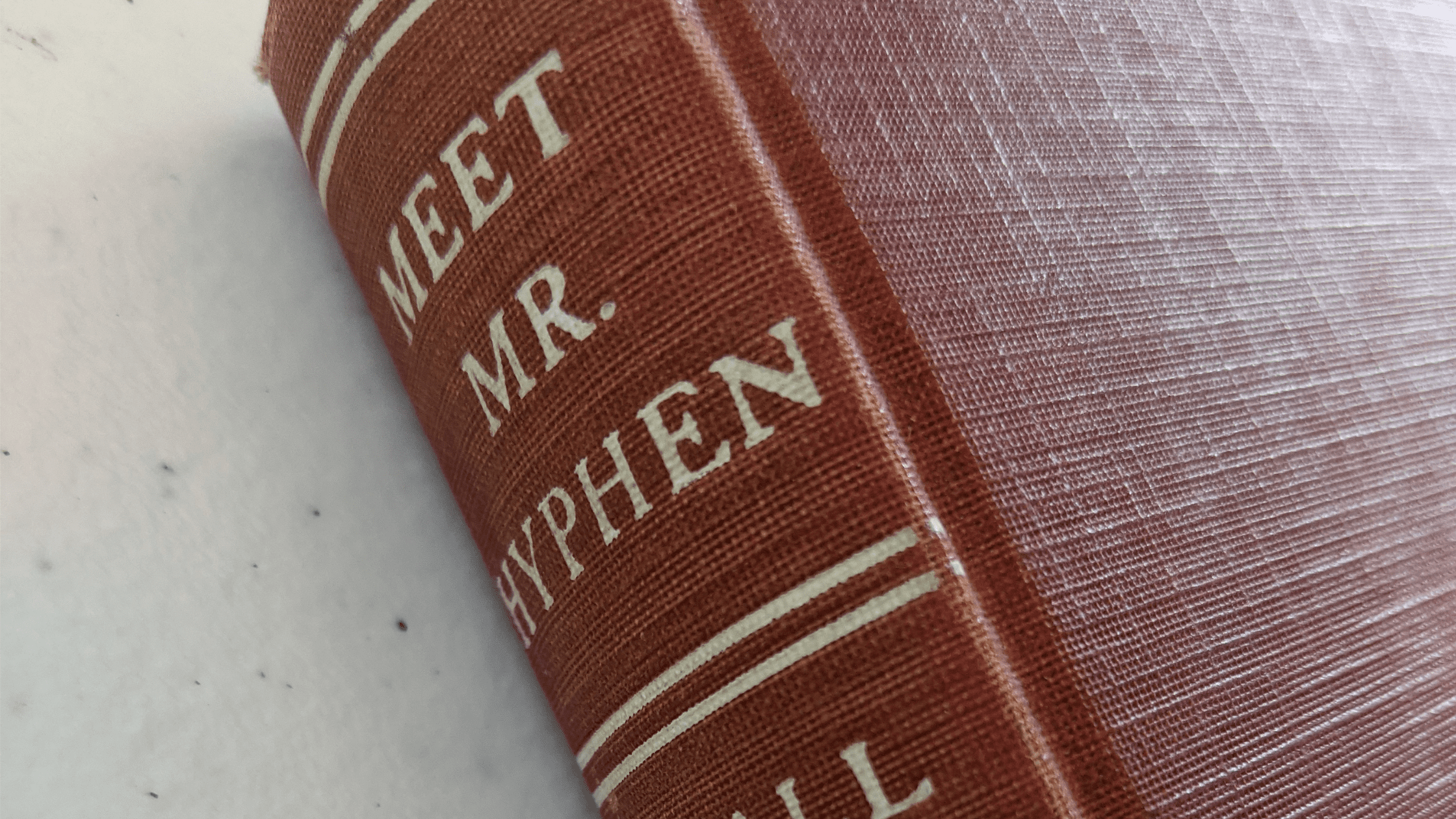

My copy of Meet Mr. Hyphen is a handy five-by-seven hardcover that smells—delightfully—of its age. The book concludes with a working guide and a “Glimpse of the Compounder’s Workshop,” both of which can be dipped into from time to time.

I’ll note that I didn’t cover Teall’s deeper analysis of compounding, such as his look at modifiers that are descriptive versus those that serve the function of identification. I still need to work my mind around that and around his other musings, but the book is there, on my shelf, and it’s not going anywhere.

If there were one thought from the book I’d tattoo on my arm, it’s probably this:

“Complete consistency is impossible. Good style is attainable.”

References

Norris, Mary. Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Teall, Edward N. Meet Mr. Hyphen (And Put Him in His Place). New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1937.

Words at Play: https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/comma-queen-meets-mr-hyphen.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]