Signing a contract can be intimidating. What am I getting into here? What might be lurking in the fine print?

When it comes to the author–editor relationship, contracts can reassure authors

- that they’ve chosen the right editor

- that the editor will provide the services they want

- that the pay and delivery schedule will meet their expectations

The Right Editor for You

Authors find editors in all kinds of ways, and if you poke around social media for a minute or two, you’ll probably come across authors asking where they can go to find a good editor.

Editors may be referred by other authors (editors love this).

Authors may find editors blind on the internet or through resources such as the Editorial Freelancers Association (of which I’m a member).

Authors may even turn to friends who love to read and regularly point out grammar miscues on Facebook (but please don’t point out grammar miscues on Facebook).

Wherever an author finds an editor, the contract is a sign of the editor’s professionalism. The contract says the following to the author:

- “I am a professional, I take my job seriously, and I will treat you in a professional manner.”

- “I want to be absolutely clear on the work that you want me to do, and I want you to be absolutely clear on the work I’m doing.”

- “I want to prevent any misunderstandings on the cost of the work or when you can expect the work to be delivered.”

Whether your editor is an old friend or a complete stranger, contracts set the business transaction off on the right foot and preserve the relationship between the parties by preventing misunderstandings.

With something as important as a manuscript an author has toiled over, better safe than sorry is a good approach for everyone involved.

The Services You Want

An author’s view of the kind of editing that should be done on a manuscript can be very different from the editor’s.

Authors and editors may even have different definitions for what is entailed by the different levels of editing: developmental editing, line editing, copyediting, and proofreading. (No surprise here, because editors often have different definitions themselves.)

Authors might not even be aware there are different levels of editing, so prework discussions leading to the contract can be extremely informative.

For example, the contract can prevent an author from thinking the copyeditor will perform Big Picture structural work on a manuscript when the copyeditor thinks he will be editing for grammar, spelling, punctuation, style, and consistency only.

No Surprises

Unspoken expectations lead to trouble, especially when it comes to money and the nature of the work involved.

A contract may specify the type of file that will be supplied to the editor (an editor may be expecting a Word document when the author is planning to send a PDF for markup or share a Google document).

A contract might say that the work will be billed based on the supplied word count and not the word count of the edited document (often much lower), or a contract may spell out a project fee and a pay schedule.

Either way, addressing payment expectations (including the deposit and methods of payment) avoids one of the greatest sources of contention.

In addition, an author might expect that the editor’s fee includes a full review of the edited manuscript after the author has addressed comments and accepted and rejected changes, whereas the editor might see this as a separate charge.

What happens when the author or editor has to pull out of a project, for whatever reason? This can be covered in the contract too.

Another thing to keep in mind is that if authors see something they don’t like in the contract, they are free to raise the issue with the editor and are encouraged to do so.

After all, editors and authors are working toward a common goal: to make the author’s manuscript as good as it can be.

Contracts help achieve this goal and reassure both parties that their expectations are being met.

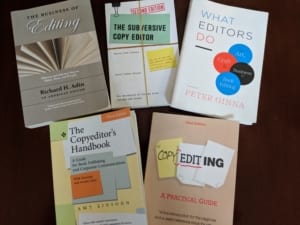

(For more on contracts and setting fees, The Paper It’s Written On by Karin Cather and Dick Margulis and The Science, Art and Voodoo of Freelance Pricing and Getting Paid by Jake Poinier, aka Dr. Freelance, are excellent resources.)

About James Gallagher:

James Gallagher is a copyeditor and the owner of Castle Walls Editing LLC. To view a sample contract or to find out how James can help with your writing projects, email James at James@castlewallsediting.com.

References:

Cather, Karin, and Dick Margulis. The Paper It’s Written On: Defining Your Relationship with an Editing Client. New Haven, CT: Andslash Books, 2018.

Poinier, Jake. The Science, Art and Voodoo of Freelance Pricing and Getting Paid. Phoenix, AZ: More Cowbell Books, 2013.