Blog

-

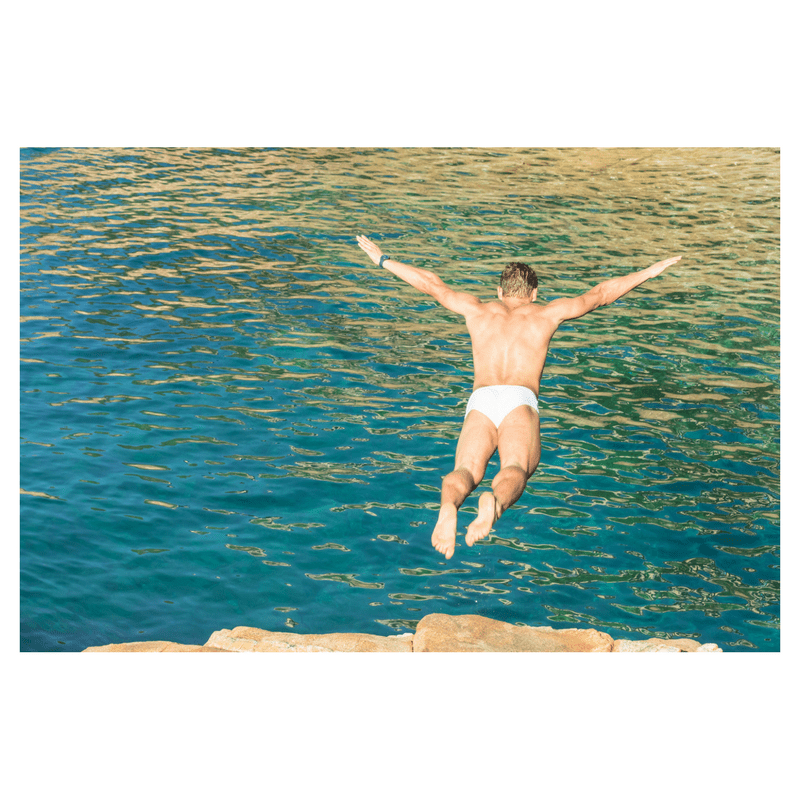

Taking the Plunge: Running an Editing Business

Last Wednesday I said my goodbyes as senior editor at Recorded Books and embarked on a new life running an editing business. Even after fourteen years with a company I love . . . Even after forming personal and professional relationships I hope will continue indefinitely . . .Even after spending nearly a third of my life as a Recorded Books employee . . .Even after all that, those first steps into my new endeavor felt . . .

-

Book Rec: ‘Vex, Hex, Smash, Smooch’ by Constance Hale

Wired Style and Sin and Syntax author Constance Hale inspires an infectious appreciation for verbs in Vex, Hex, Smash, Smooch: Let Verbs Power Your Writing. While the book dropped in 2012, its not-so-hot-off-the-presses status doesn’t diminish its readability, power, or utility for writers and editors. Deep into the book, Hale relates that, while serving as […]

-

The Five Stages of CMOS 16 Grief

The seventeenth edition of the Chicago Manual of Style will soon be in the hands of editors everywhere. The sixteenth edition was released way back in 2010, so you can’t blame Ol’ Sixteen for thinking its reign would last forever. Let’s check in on how it’s handling the transition (and you can click here for a […]

-

Toward (Towards?) a Better Tomorrow

Big changes lie ahead for me personally and professionally. I’ve made some life-altering decisions, and I feel good about those decisions. There’s uncertainty, sure, but I feel good about that too. I’ve lost a lot in life. My mother and sister died when I was 17. Not long thereafter I spent a summer watching my grandmother die of lung cancer. I’ve lost too many friends too soon. In many ways I lost my father, who died just before the new year, long ago.

-

5 Signs an Editor Has Been at Work

Sometimes I’ll be reading happily along and find myself tipping my cap to another editor for the care taken with a particular usage. For just a moment, that editor is there, ghostlike, almost visible through the page. You don’t need an EMF meter or full-spectrum camera to spot an editor, nor do you have to worry about ectoplasm on your favorite book. The following are five signs an editor has been at work.

-

What Level of Editing Do You Need?

You’ve completed your manuscript and are eager to send it out into the world, but for your sake (and for the sake of your work) it’s important to determine the level of editing you require.

-

Sentences That Pack a Wallop

Sentences seem like simple enough beasts. You have a capital letter, one or more words, and a period (or possibly a question mark or exclamation point or ellipsis). You usually have a subject and predicate (noun and verb).